Japanese antique chests and cabinets are used as sofa tables, bedside cabinets, study and bedroom chests, sideboards, kitchen dressers and all manner of storage in the home. Japanese furniture radiates character and charm whilst being incredibly functional.

Combining simple designs and shapes, sliding doors and secret hidden drawers, along with practical configurations of drawers and cupboard spaces; portability is also considered and reflected in handles and light weight timbers.

Historically, form followed function in the evolution of design in Japanese furniture. Practicality and space were paramount in the minds of Japanese carpenters, who considered the choice of timbers for each part of the construction process according to their properties and the structural requirements each of the parts. Japanese antique furniture is simple, functional and designed with ease of movement or portability in mind. Nearly all chests have handles so they can be easily moved on poles or carried by hand and are often constructed in two parts. Each piece is usually made from between one and three different timbers for different aspects of the piece frame, panelling and drawer and door facades with each timber being appropriate for different purposes.

The development of Japanese furniture grew out of the early use of simple lidded boxes or woven baskets for the storage of kimono and personal possessions. While the aristocracy used simple open shelves quite early on as well as trunks for travelling and campaigns, the use of trunks and baskets for storage of clothing, across all social groups, was common until the late C17th C18th when the merchant classes evolved and coastal trading flourished.

The new merchant classes had a need for chests cho-dansu or choba-dansu for storage of all kinds including chests for keeping their paperwork, tea making equipment and small valuables. Later chests for clothing tansu became more common and there were even chests for travelling salesmen to carry.

Stair cases kaidan dansu were not built as part of the structure of a house but as individual units of furniture, custom made to fit the house, with built in drawers and cupboards, often made in two parts for ease of movement.

In substantial households in rural or provincial areas and when household possessions, clothing and decorations were changed seasonally, chests on wheels or kuruma dansu were a popular method of moving goods between the main house and a kura - the earthquake and fire resistant thick walled store room - a substantial store room where goods were well protected for safe keeping, often along with the precious rice harvest.

In the Edo period when the urban population grew exponentially, many more kuruma chests were to be seen in Edo (Tokyo) especially as the aristocracy were obliged by decree of the Shogun to spend a certain amount of time each year there to ensure they did not conspire to rise up against him. This led to the popularity of the wheeled storage chest amongst the general populace as the design was seen as a pragmatic method of fleeing quickly from fires with possessions, following in the aftermath of the frequent earthquakes.

Kuruma chests became illegal in built up areas after the conflagration, the Great Fire of Tokyo, mid C17th. Many perished after one notable 'traffic' jam as kuruma dansu clogged the narrow streets hampering the effort of fire fighters to quell the flames.

However, it was still possible to own and use them outside the urban centres and so the tradition continued in the rural areas.

The following book is an excellent resource:

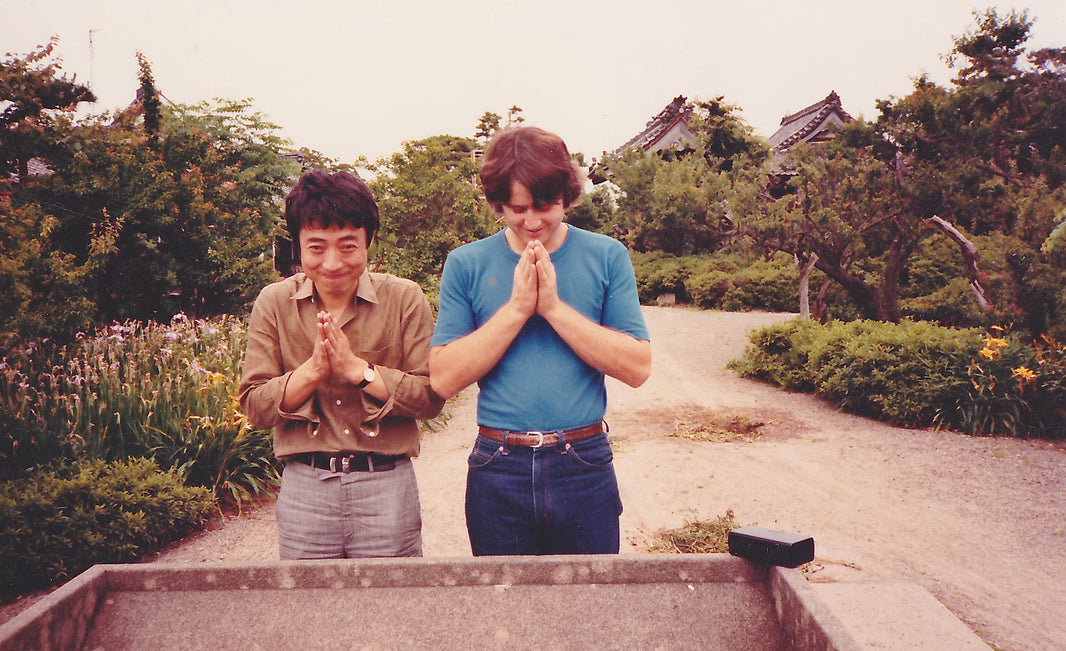

Tansu: Traditional Japanese Cabinetry, Ty & Kiyoko Heineken. Wetherhill: Tokyo, 1981.